– 10 year old FS Boston Terrier presented for a pre-op echo due to the presence of a grade 3/6 systolic heart murmur; pet is asymptomatic

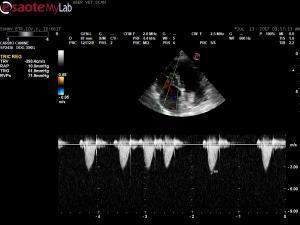

– echo shows a mass that appears to be coming from the arotic wall but I can’t say for sure it is not coming from the right main pulmonary artery branch

– also appears to be either invading the LA or pressing on it primary ddx: chemodectoma

– this pet also has MMVD and I documented pulmomary hypertension at approx. 62 mmHG

– 10 year old FS Boston Terrier presented for a pre-op echo due to the presence of a grade 3/6 systolic heart murmur; pet is asymptomatic

– echo shows a mass that appears to be coming from the arotic wall but I can’t say for sure it is not coming from the right main pulmonary artery branch

– also appears to be either invading the LA or pressing on it primary ddx: chemodectoma

– this pet also has MMVD and I documented pulmomary hypertension at approx. 62 mmHG

– aortic and pulmonic max flows wnl; blood work mild elevations ALP, ALT; mild neutrophilia HW NEG

– I am trying to stage this one and got a very large LA measurement but I think I measured the mass that was in the way; looking at the left apical view, I am no convinced the LA is too large – thoughts?

I decided not to proceed with the dental procedure

– also what to do about the PAH? the pet is currently asymptomatic – could it be related to the mass?

Comments

The position fits

The position fits chemodectoma. I have found PHT frequently and systemic HT in these cases. They are slow growing. Here is the latest info on herat based tumors I gift the forum the chapter from the curbside guide on cardiac neoplasia.

Tx any hypertension or pht and suppoortive vcare or paroxysmal arrythmias. If any passive congestion form cvc obstruction then hypoxia may cause LE elevations.

https://sonopath.com/products/book

Pericardial Effusion and Cardiac Neoplasia

http://www.sonopath.com/CardiacNeoplasiaEffusion

Description:The pericardiumis a fibrous sac that encloses the heart and the great vessels—aorta, pulmonary artery, proximal pulmonary veins, and vena cava—located at the heart’s base. It is attached caudally to the diaphragm and under normal circumstances contains 1-15 mL of fluid. The latter is comprised of phospholipids that lubricate the heart and allow it to expand and contract without generating friction. The pericardium also fixes the heart, prevents excess motion, and links the diastolic distensibility of the ventricles, thus limiting the degree to which either the left or the right ventricle will distend during diastole. When there are acute changes in venous return (i.e., during exercise), the pericardium plays a critical role in limiting ventricular filling. In cases of chronic cardiac enlargement, the pericardium also becomes distended, and its ability to limit ventricular filling, especially when the heart is at rest, becomes compromised. Pericardial tamponade occurs when there is a rapid accumulation of fluid and the pressure inside the pericardium increases significantly. With tamponade, ventricular filling is restricted and cardiac output is decreased. The right atrium and ventricle are the most vulnerable to this condition as these compartments have thinner walls and a lower pressure.

Etiology:Causes of pericardial effusion include:

The majority of neoplastic masses consist of hemangiosarcoma and heart-based tumors (chemodectomas or ectopic thyroid adenocarcinoma). Idiopathic pericardial effusionis a diagnosis of exclusion; the effusion is typically hemorrhagic. Approximately 50% of dogs will be cured with a single pericardiocentesis, while some dogs will require multiple pericardiocenteses as well as surgery.A peritoneal-pericardial diaphragmatic hernia is a congenital hernia seen in dogs and cats in which the abdominal contents (i.e., liver, small intestine, spleen, stomach) herniate into the pericardial sac. Constrictive pericarditis is an uncommon condition in which a non-distensible, thickened, fibrotic pericardium develops over time.

Clinical Signs:One will observe the following clinical signs, which often present in combination: ascites, lethargy, exercise intolerance, pale mucous membranes, weak pulses, pulsus paradoxus, and respiratory distress.

Diagnostics: Survey radiographs will reveal hepatomegaly, cardiomegaly (generalized or sectorial globoid), and small pulmonary vessels. Pulmonary edema is typically not found, although one may discover concurrent pulmonary metastatic disease. An ECG will show electrical alternans or small complexes, but often the changes are very subtle and difficult to detect.

Echocardiography is usually considered the gold standard for diagnosing pericardial effusion. Findings include:

Cytology is helpful in the diagnosis of lymphoma, septic pericarditis, and idiopathic effusion, but not in cases of neoplasia.

According to a study that found troponin l levels to be higher in dogs with neoplastic pericardial effusion, the cardiac troponin I assay can be helpful in the diagnosis hemangiosarcoma.

Prognosis:

References:

Cagle LA, Epstein SE, Owens SD, et al. Diagnostic yield of cytology analysis of pericardial effusion in dogs. J Vet Int Med 2014;28:66-71.

Feigenbaum H. Pericardial disease. In: Feigenbaum H, ed. Echocardiography, 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 1994:556-588.

Jackson J, Richter KP, Launer DP. Thorascopic partial pericardectomy in 13 dogs. J Vet Int Med 1999;13:529-33.

Johnson MS, Martin M, Binns S. A retrospective study of clinical findings, treatment and outcome in 143 dogs with pericardial effusion. J Small Anim Prac 2004;45:546-52.

Kienle RD, Thomas WP. Echocardiography. In: Nyland TG and Mattoon JS, eds. Small Animal Diagnostic Ultrasound, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2000:354-423.

Miller MW, Sisson DD. Pericardial disorders. In: Ettinger SJ and Feldman EC, eds. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2000:923-36.

Rajagopalan V, Jesty SA, Craig LE, et al. Comparison of presumptive echocardiographic and definitive diagnoses of cardiac tumors in dogs. J Vet Int Med 2013;27:1092-96.

Shaw SP, Rozanski EA, Ruhs JE. Cardiac troponins I and T in dogs with pericardial effusion. J Vet Int Med 2004;18:322-24.

Sidley JA, Atkins CE, Keene BW, et al. Percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy as a treatment for recurrent pericardial effusion in 6 dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2002;16:541.

Sisson D, Thomas WP. Pericardial disease and cardiac tumors. In: Fox PR, Sisson D, Moïse NS, eds. Textbook of Canine and Feline Cardiology, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1999:679-701.

Sisson D, Thomas WP, Reed J, et al. Intrapericardial cysts in the dog. J Vet Int Med 1993;7:364-69.

Thank-you EL. Considering

Thank-you EL. Considering this dog is completely asymptomatc, would you reach for sildenifil at this stage?

Hmm… not sure what Peter

Hmm… not sure what Peter would do here but my personal rule is if TR is > 3.8 m/sec then I use sildenafil regardless if clinical or not because you never know when the first clinical sign is going up the stairs syncope and death:(.

But I go to sildenfail in this scenario or if clinical signs of ex intollerance and TR > 3.5 m/sec +/- hepatic vein dilation. So take this as an “EL consensus” between my ears but Im sure there would be a wide ranged discussion in cardioo rounds on this.

Peter? Thoughts?

Hi!

Very difficult to say

Hi!

Very difficult to say what kind of tumor it is – I agree, chemodectoma/paraganglioma is most likely, but a study (Rajagopalan et al. JVIM 2013) has shown that diagnosing a tumor based on where it appears on ultrasound can be very inaccurate. What about the abdomen?

I think that this tumor likely obstructs pulmonary venous inflow – and this can cause passive pulmonary hypertension. Furthermore, this animal has DMVD. Also, the tumor could cause airway obstruction and increase PA pressures by causing chronic hypoxia. If the tumor invades the pulmonary artery, obstruction as well as thrombembolism can cause pulmonary hypertension.

Given the overall appearance of the heart (degenerative valve disease with enlarged left atrium and pulmonary hypertension) I would likely start Pimo first and re-check the patient in 1-2 months and add Sildenafil then if necessary – but this is not a consensus (as Eric said) but my personal way to go here. Maybe Eric’s right and I’m wrong but this is rather personal experience and opinion without any evidence. Anyway, I don’t think that is makes very much of a change here since the main problem is a mechanical one that cannot be addressed neither with pimo nor with sildenafil. Still, I woudl use Pimo first in this setting.

Hi!

Very difficult to say

Hi!

Very difficult to say what kind of tumor it is – I agree, chemodectoma/paraganglioma is most likely, but a study (Rajagopalan et al. JVIM 2013) has shown that diagnosing a tumor based on where it appears on ultrasound can be very inaccurate. What about the abdomen?

I think that this tumor likely obstructs pulmonary venous inflow – and this can cause passive pulmonary hypertension. Furthermore, this animal has DMVD. Also, the tumor could cause airway obstruction and increase PA pressures by causing chronic hypoxia. If the tumor invades the pulmonary artery, obstruction as well as thrombembolism can cause pulmonary hypertension.

Given the overall appearance of the heart (degenerative valve disease with enlarged left atrium and pulmonary hypertension) I would likely start Pimo first and re-check the patient in 1-2 months and add Sildenafil then if necessary – but this is not a consensus (as Eric said) but my personal way to go here. Maybe Eric’s right and I’m wrong but this is rather personal experience and opinion without any evidence. Anyway, I don’t think that is makes very much of a change here since the main problem is a mechanical one that cannot be addressed neither with pimo nor with sildenafil. Still, I woudl use Pimo first in this setting.

Thank- you Peter. Not gonna

Thank- you Peter. Not gonna FNA this one : )